There has been enormous speculation recently about how repetitive concussions could lead to dementia and/or early Alzheimer’s (or Alzheimer like symptoms). Loss of brain function with repetitive blows to the head does not seem like it would be debatable, but many hesitate to take a stand on it because of “lack of evidence”. After all, it could just be coincidence that people get dementia in their late 40s or early 50s after a long career in a sport or activity that repetitively causes glial damage without having time for adequate recovery. But what do we know? So let’s take a look at some data.

According to the CDC, the incidence of sports-related concussions has reached an epidemic level, with 1.6-3.8 million sports-related concussions occurring each year in the US alone. And that’s not even including head injuries from things like motor vehicle accidents, falls, or other blows to the head. Media headlines frequently highlight the growing problem, especially with respect to repeated concussions and long term effects. It’s not new news that severe brain injuries, or even that repeated mild or moderate brain injuries, can cause problems down the road, but what about a single, mild concussion without loss of consciousness (LOC)?

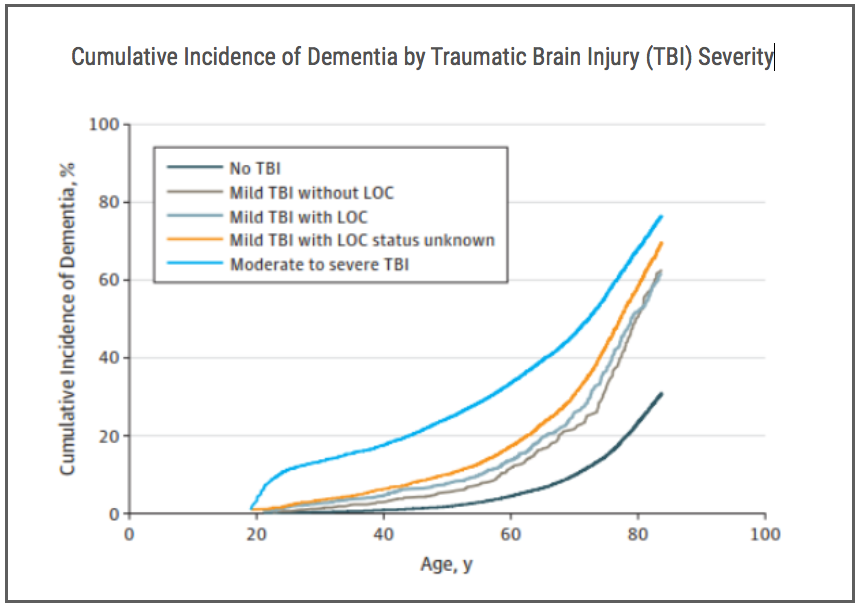

The figure above shows unadjusted cumulative incidence of dementia (age at dementia diagnosis) is shown as a function of TBI severity. After adjustment for demographics, medical conditions, and psychiatric diorders, there was a dose-response relationship between TBI severity and dementia diagnosis with hazardous ratios of 2.36 (95% CI, 2.10-2.66) for mild TBI without loss of consiousness (LOC); 2.51 (95% CI, 3.05-3.33) for mild TBI with LOC status unknown, and 3.77 (95% CI, 3.63-3.91) for moderate to severe TBI.

Given the nature of the injury, it can be hard to study. For obvious reasons, you can’t do a placebo controlled trial and give people a concussion to see what happens. Even doing an observational study can be difficult due to differences in variables such as where on the head someone was hit, how many concussions had been sustained previously, and relying on self-reported diagnosis/severity of the injury. Despite these limitations, a recent study published in JAMA was able to find an interesting link between mild TBI/concussion and dementia.

Instead of relying on self-reported data, the authors used data from the Veteran’s Health Administration to find all reported TBIs sustained between October 1, 2001 and September 30, 2014 (n=178,779). Patients were divided into groups based on severity of TBI: mild without LOC, mild with LOC, mild with no reporting of LOC, and moderate to severe, with a control group from the same population with no reported concussions during that time frame.

The authors then looked at the incidence of diagnosed dementia following TBI and found a significantly higher rate among all TBI groups compared to the control group. Even after adjusting for demographics, medical conditions, and psychiatric disorders, in the mTBI group with no LOC, incidence of dementia was 2.36 times more likely than in the control group. The association was positively correlated with severity of TBI, with the mTBI with LOC group and moderate/severe TBI group 2.51 and 3.77 times more likely to develop dementia, respectively.

While there are some notable limitations of the study, such as no discrimination between number of TBIs sustained, both within and prior to the sample period, the large sample size and positive correlation between severity and risk of dementia suggest that the correlations reported are unlikely to be due to chance. This suggests that the hazards related to even a mild concussion that are increasingly likely on the sports field may have even more long-term effects than previously thought.

Could you measure the neurophysiological impact of any concussions that you might have sustained? Most methods are sensitive only to about 2-3 weeks beyond date of concussion, but we were part of a study that made observations of long term effects of concussions. So, the answer is, of course, yes, the Brain Gauge demonstrated differences in a post-concussion group 16 months post-concussion, but that is the topic of our next post.